Tapu and noa

Tapu is the strongest force in Māori life. It has numerous meanings and references. Tapu can be interpreted as ‘sacred’, or defined as ‘spiritual restriction’, containing a strong imposition of rules and prohibitions. A person, object or place that is tapu may not be touched or, in some cases, not even approached.

Noa is the opposite of tapu, and includes the concept of ‘common’. It lifts the ‘tapu’ from the person or the object. Noa also has the concept of a blessing in that it can lift the rules and restrictions of tapu.

To associate something that is extremely tapu with something that is noa is offensive to Māori.

| Papatūānuku cheese

Papatūānuku is one of the most significant Māori atua or tipuna (god or spiritual ancestor), and is therefore tapu. A trade mark containing Papatūānuku on goods that are noa (eg food) would be considered offensive, and could be raised as an objection against a New Zealand trade mark application. |

|

Māori world view and values

Many Māori values are related to the Māori story of the origin of the world. In the relationship between Ranginui (the sky father) and Papatuanuku (the earth mother) and their children, from whom all living things are believed to descend. All plants and animals, according to the Māori world view, therefore share a sacred (tapu) origin.

The relationship between people and all living things is characterised by a shared origin of life principle referred to as mauri. Any acts undermine or disrespects mauri is therefore objectionable.

Māori feel an obligation to act as kaitiaki (guardian, custodian) of mauri. Mauri is not limited to animate objects - a waterway, for example, has mauri, and a mountain has mauri by virtue of its connectedness to Papatūānuku.

Values that enhance and protect mauri are:

- Tika: truth, correctness, directness, justice, fairness, righteousness,

- Pono:

- Aroha: affection, sympathy, charity, compassion, love, empathy.

Inappropriate inference

It would be inappropriate to associate some goods and services with Māori elements. For example, alcohol, tobacco, genetic technologies, gaming and gambling all have the potential to devalue Māori people, culture and values.

Associating Māori elements with these types of goods and services could be considered offensive. Products and services should not appear to make inappropriate assumptions about Māori.

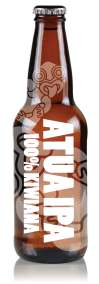

| Inappropriate inference: Atua IPA ale

Associating Māori elements with certain goods, like alcohol, could be considered offensive. |

|

These historical examples of inappropriate inference would not be acceptable today for many reasons, including the combining of noa and tapu:

Historical examples not acceptable today

1914 1914 |

1927 1927

|

1935 1935 |

Images from Well Made New Zealand: a Century of Trademarks. Richard Wolfe, Reed Methuen, 1987.

Māori to English translation

Some Māori words and concepts can be translated into English without causing offence. However, sometimes there’s another layer of meaning or understanding that needs to be considered.

For example, the word ‘kuia’ could be translated as ‘grandmother’. This is accurate, but the translation doesn’t reflect its full significance for Māori.

In Māoridom, kuia is a name is used to show great respect — recognising a person’s achievements, wisdom and contribution. In this light, it would be offensive for kuia (tapu) to be associated with things like food and alcohol (noa) in a trade mark.

Cultural significance

Māori attribute physical, economic, social, cultural, historic, and/or spiritual significance to certain words, expressions, performances, images, places, and things. There are many cases where it would not be appropriate to copy or use a Māori cultural element, especially a traditional one.

Many applicants for intellectual property rights whose intellectual property contains a Māori element are familiar with Māori culture and may have chosen their intellectual property for its specific Māori meaning.

However, a growing number of products are referencing traditional Māori art and design, both in New Zealand and overseas. Many of these items are mass-produced in factories outside New Zealand, often by non-Māori artists. Few have an understanding of Māori culture behind them.

Even commonplace Māori words and designs should be treated with care. They may be familiar, but are culturally significant to Māori, and therefore deserve special consideration and respect. Consider the hei tiki:

| New Zealand hei tiki (tiki)

Familiar Culturally significant Special consideration and respect Using hei tiki for particular products or services may be offensive to Māori. This can be raised as an objection against your New Zealand trade mark or design application, and may impact market sales. |

|

No matter how familiar you are with Māori culture, it is worthwhile spending some time researching the cultural significance of your proposed intellectual property. This might include contacting the appropriate Māori elders or iwi representatives to:

- discuss your intended application,

- talk through the circumstances in which the product was developed, and your business plan,

- ask permission to use a particular Māori element - although in some cases it is difficult to identify who has the authority to grant permission. This could also work against the need to keep the intellectual property confidential until it has been protected.

Two items with Māori cultural significance are protected by law in New Zealand:

- Ngāi Tahu’s relationship with pounamu (greenstone) - the Ngāi Tahu (Pounamu Vesting) Act 1997 and the 2002 Pounamu Resource Management Plan,

- the haka ‘Ka Mate’ - the Haka Ka Mate Attribution Bill, acknowledging the haka as a taonga of Ngāti Toa Rangatira).

However, for most Māori elements, there aren’t explicit rules or a one-size-fits-all process to follow.

Māori artwork and design

Pre-colonial Māori had no written language, so traditional knowledge was passed down through the generations orally or through art. Full of meaning and symbolism, traditional Māori art and design form an important part of Māori identity and culture. Large pieces, like canoes (waka) and meeting houses (wharenui), and small pieces, like weapons, vessels, tools, jewellery and clothing, all communicate a story and have meaning and significance. Each shape, colour and material was carefully selected for its cultural or spiritual meaning.

Also see Māori imagery.

Māori tikanga (the 'right' way to do things)

Māori artists often dedicate themselves to studying a specific art form. Part of this study includes learning tikanga, or the ‘right’ way to do things. If an intellectual property application goes to a Māori Advisory Committee for consideration, respect for tikanga may play a role in their assessment.

Using or commissioning Māori artwork and design

When using or commissioning Māori artwork or designs, consider using an artist or designer who is familiar with traditional Māori culture and tikanga. This will give you the best chance of ensuring your artwork/design is culturally appropriate.

Traditional Māori design elements

Below are some traditional Māori icons and their meanings. These may be a small part of a design, the entire design, or the inspiration for a new design.

Traditional Māori icons

|

|

|

| Koru | Hei matau | Manaia

|

| The koru depicts an unfolding fern frond. It symbolises new beginnings, growth and harmony | The hei matau or fish hook depicts abundance, strength and determination. It is also said to be a good luck charm for those journeying over water. | The manaia depicts a spiritual guardian. It has the head of a bird, the body of a man, and the tail of a fish. A manaia provides spiritual guidance and strength. |

|

|

|

| Pikorua | Toki | Roimata |

| The pikorua symbolises the joining together of two people or spirits. It is also said to represent life’s eternal paths. | The toki is a stylised adze that represents strength, control and determination. | Roimata means “tear drop” and symbolises sadness or grief. It was sometimes given as a gift to comfort or console. |

Māori traditional knowledge

Traditional knowledge is a living body of knowledge, typically passed from generation to generation, that may be linked to cultural identity. The nature of traditional knowledge as a living and developing thing can mean that it is difficult to protect using intellectual property rights.

For example, in the case of patents and designs, the invention or design must be new and/or original, whereas inventions derived from traditional knowledge may be neither new nor original. Also, intellectual property rights are owned by individuals or an identifiable commercial entity, whereas traditional knowledge belongs to a collective group, and may have developed over centuries.