In this practice guideline

Māori advisory committee and Māori trade marks

Introduction

Section 17 of the Trade Marks Act 2002 (“the Act”) provides that the Commissioner of Trade Marks (“the Commissioner”) must not register a trade mark if, in the Commissioner’s opinion, its registration or use would be likely to offend a significant section of the community, including Māori.

The Act requires the Commissioner to establish an advisory committee.1 The function of that committee is to advise the Commissioner on whether the proposed use or registration of a trade mark that is, or appears to be, derivative of a Māori sign (including text and imagery) is, or is likely to be, offensive to Māori.2

The advisory committee was established in 2003, and is now known as the Māori Trade Marks Advisory Committee (“the Committee”).

All trade mark applications are assessed to determine whether the trade mark is, or appears to be, derivative of a Māori sign. A trade mark that consists of or contains an element of Māori culture, or that appears to be derivative of an element of Māori culture, is considered a Māori sign, or derivative of a Māori sign.

All applications to register such trade marks are referred to the Committee, so they can advise the Commissioner on whether the marks are likely to offend Māori.

There is no additional charge for a trade mark application to be referred to and reviewed by the Committee.

The purpose of these guidelines is to:

- help applicants identify whether the trade mark in their application is likely to be assessed as a mark that is, or appears to be, derivative of a Māori sign.

- explain the examination process for applications to register trade marks that are, or appear to be, derivative of Māori signs.

- increase transparency about matters the Committee may take into account, when advising the Commissioner on whether the proposed use or registration of a trade mark is, or is likely to be, offensive to Māori

Applicants are encouraged to consider the guidance in these guidelines, and to obtain specialist advice or engage with Māori before adopting a trade mark that contains elements of Māori culture or appears to be derivative of elements of Māori culture. However, these are not statutory requirements. IPONZ will consider all trade mark applications for registration, including those where specialist advice has not been sought and engagement with Māori has not taken place.

Background

Any trade mark has the potential to be a Māori sign, or to appear to be derivative of a Māori sign, including word marks, image marks, animation marks, shape marks, colour marks, sound marks and smell marks.

A trade mark that consists of or contains an element of Māori culture, or that appears to be derivative of an element of Māori culture, is considered a Māori sign or derivative of a Māori sign.

Elements of Māori culture include anything sourced and generated from a Māori world view, te ao Māori. These include words or images that are, make reference to or include:

- Māori words, proverbs, expressions of language, dialect, genealogical information (whakapapa), or naming conventions

- Māori names, including Māori whānau, hapū, iwi or marae names

- Māori people, places, characters, protocols

- Māori history, cultural stories, historical accounts, songs, dance, cultural expressions that may or may not be in the public domain

- Toi Māori – art, carving, moko and tā moko, raranga, clothing and adornments, visual arts, games, both traditional and modern cultural expressions

- Taonga Māori – Te Reo Māori, landmarks, whakapapa, photographs, heirlooms, taonga tuku iho, tribal landmarks, artefacts in collections, flora and fauna (native trees, birds, taonga species)

- Specific whānau, hapū or iwi tribal land, waterways, mountains, social systems and structures

- Mātauranga

Using elements of Māori culture in a trade mark is a unique way of indicating that the goods and services come from New Zealand. However, trade marks that contain, or appear to derive from, elements of Māori culture need to be used sensitively and with respect to avoid inadvertently causing offence.

Sensitive and respectful use of elements of Māori culture requires an understanding of Māori culture, including Te Ao Māori and mātauranga.

1. Te Ao Māori and mātauranga

1.1. General concepts

Te Ao Māori, mātauranga and tikanga inform how Māori use Māori words, Māori images and other elements of Māori culture.

If the use or registration of a trade mark that contains, or appears to be derived from, Māori elements is inconsistent with a Te Ao Māori view and the values and principles that underpin mātauranga, there is a risk the trade mark’s use or registration may be offensive to Māori.

1.1.1. Mātauranga is a unique taonga (treasure). Most commonly translated as Māori knowledge, mātauranga is a broad term referring to the body of traditional knowledge that was first brought to New Zealand by Māori. It is a dynamic and evolving body of knowledge passed from generation to generation, and so it may refer to historic and modern-day Māori values, perspectives, and creative and cultural practices, including Te Reo Māori ‒ the Māori language.

1.1.2. Mātauranga is a body of knowledge that whānau, hapū, iwi, and other Māori groups can utilize, share, and benefit from, but those rights of use also introduce a collective responsibility to use in accordance with tikanga, ensuring the taonga is honoured, and acknowledging the source of the taonga. There may also be other relevant considerations. Iwi and Māori believe they are intrinsically connected to whatever they create, and this connection cannot be severed. The new work may be assigned or shared, but maintaining the taonga status of mātauranga requires ongoing acknowledgement and maintenance of connection between the creator of the work and the work itself, when using or sharing the work. These features of mātauranga are important when considering whether to register a trade mark containing elements of Māori culture, how the mark will be used, and the goods and/or services for which the mark will be used.

1.1.3. Māori values are also aligned to Māori stories relating to the origin of the world. For some iwi and Māori, the relationship between Ranginui (the sky father), Papatūānuku (the earth mother), and their children, from whom all living things, including plants and animals, are believed to descend, share a sacred (tapu) origin.

1.1.4. The relationship between people and all living things is characterised by a shared origin of life principle referred to as mauri. Actions that undermine or disrespect mauri may be viewed as offensive.

1.1.5. Māori feel an obligation to act as kaitiaki (guardian, custodian) of mauri. Mauri is not limited to animate objects. A waterway, for example, has mauri, and a mountain has mauri by virtue of its connectedness to Papatūānuku.

1.1.6. Values that enhance and protect mauri are:

Tika: truth, correctness, directness, justice, fairness, righteousness.

Pono: to be true, valid, honest, genuine, sincere.

Aroha: affection, sympathy, charity, compassion, love, empathy.

Mana: prestige, authority, control, power, influence, status, spiritual power.

Rangatiratanga: right to exercise authority, sovereignty, self-determination.

1.2. Meanings of specific concepts

1.2.1. Te Reo Māori is the indigenous language of New Zealand and is recognised as a taonga under Te Ture Mō Te Reo Māori 2016. Te Reo Māori is an important part of Māori culture and the identity of Māori people. Te Reo Māori is also an official language of New Zealand. The incorrect or inappropriate use of Te Reo Māori may cause offence.

1.2.2. Taonga Māori is a term that refers to many cultural treasures. The use of taonga could cause offence unless done with integrity – honouring and acknowledging the taonga, taking due care, consideration, and respect.

1.2.3. Taonga species refers to native flora and fauna of New Zealand, and includes native birds, native fish, native trees, and other flora and fauna that are part of New Zealand’s unique landscape and are considered taonga. Taonga species includes endemic species that were present prior to the first European contact, indigenous and native species resident in New Zealand prior to European contact, introduced species that arrived with the migrating waka, hybrid species from one of the above, cosmopolitan species found in New Zealand boundaries, and cryptogenic species that are found within New Zealand boundaries. Many of these taonga species have their own Te Reo Māori names.

1.2.4. Kupu refers to all Māori words, which together make up Te Reo Māori. Some kupu carry special meanings for Māori, and there is generally a higher sensitivity in relation to the use of such words. Kupu that carry special meanings for Māori are also considered to be taonga.

1.2.5. Whakapapa means genealogy or lineage. Māori consider that words and images have whakapapa and believe it is important to acknowledge the origins of words and images.

1.2.6. Tapu / Noa

1.2.6.1. Iwi and Māori attribute spiritual and cultural significance to everything, including words, images, and locations. It is beneficial to have some understanding of Māori culture and protocols to avoid causing offence inadvertently. This includes understanding the concepts of tapu and noa, perhaps some of the most complex of Māori concepts to understand.

1.2.6.2. “Tapu” is the strongest force in Māori life. It has numerous meanings and references. Tapu can be interpreted as “sacred”, or defined as “spiritual restriction” or “implied prohibition”, which contains a strong imposition of rules and prohibitions. A person, object, or place which is tapu may not be touched or come into human contact. In some cases, it is not appropriate to approach the person, object, or place.

1.2.6.3. “Noa”, on the other hand, is the opposite of tapu and includes the concept of common; it lifts the “tapu” from the person or the object. Noa is also used to refer to the concept of a blessing, in that an act of noa can lift the rules and restrictions of tapu.

1.2.6.4. Example of Tapu/Noa – Māori consider rangatira (chief) and whakairo (carving) to be tapu, whereas Māori consider food or cigarettes to be noa. Therefore, the association of a chief or depictions of carvings with foodstuffs and cigarettes could be offensive to Māori. To associate something that is extremely tapu (rangatira or whakairo) with something that is noa signifies an attempt to lift the tapu of the rangatira and whakairo – which could offend Māori.

2. The Act and the Māori Trade Marks Advisory Committee

2.1. Introduction

2.1.1. The Act provides the ability for an individual person, company, or other legal entity to obtain exclusive rights to use a trade mark and to enforce that right against unauthorised third parties. This notion of individual ownership contrasts with Māori world views, values, and cultural practices, because the owner has the exclusive right to use, sell, assign, or give the rights away. Holding individual rights in this manner is fundamentally inconsistent with Māori world views, values, and cultural practices, where collective ownership and collective responsibilities are paramount.

2.1.2. These contrasting perspectives were considered in the recommendations of the Waitangi Tribunal in the Ko Aotearoa Tēnei report (‘Wai262 report’).

2.1.3. The issues raised in the Wai 262 claim have been raised by indigenous peoples around the world for many years. Māori first raised these issues when the Crown commenced a review of the Trade Marks Act 1953 in 1991. To investigate these issues, the Crown established a Māori Trade Marks Focus Group, who wrote and published Māori and Trade Marks: A Discussion Paper. This paper made several recommendations on amending the Trade Marks Act to address the concerns of Māori. These recommendations were considered during the drafting of the current Act. One of the outcomes was section 17(1)(c) of the Act, which prevents the Commissioner from registering a trade mark if the Commissioner considers its use or registration would be likely to offend Māori.

2.2. The Māori Trade Marks Advisory Committee

2.2.1. The Committee comprises several members, one of whom acts as the Committee chair. The members of the Committee have a deep understanding of mātauranga and tikanga Māori. The Committee plays an important role in ensuring the Commissioner does not register trade marks that contain, or are derivative of, a Māori sign where their use or registration is likely to be offensive to Māori.

2.2.2. The members of the Committee hold extensive expertise across a wide range of areas, including culture, art, and business. The Committee members work together to advise the Commissioner on whether the use and registration of trade marks is likely to offend Māori.

2.2.3. The Commissioner considers the advice received from the Committee in relation to an application but is not required to follow that advice. The Commissioner will consider the Committee’s advice and then determine whether a section 17(1)(c) objection should be raised.

2.2.4. Māori views are diverse. A consequence of this is that there is no ‘one size fits all’ perspective in Māori culture. The Committee considers each application to register a trade mark that contains (or appears to derive from) Māori elements on a case-by-case basis, considering and weighing Māori perspectives that are relevant in each instance, before giving its advice to the Commissioner.

3. Adopting a trade mark that includes elements of Māori culture

3.1. Consider seeking specialist advice or engaging with Māori

3.1.1. It is a good idea to seek specialist advice or engage with Māori when planning to use elements of Māori culture in a trade mark. This is not a statutory requirement, however it is highly recommended if you wish to avoid offending Māori inadvertently.

3.1.2. The use of elements of Māori culture in trade marks should be done with sensitivity and respect to avoid causing offense. As part of this, it is important to consider the context in which the trade mark is or will be used, including the specific goods or services the mark will be used on.

3.1.3. To avoid causing offence, applicants are encouraged to conduct due diligence to ensure that any current or future use of Māori elements in a trade mark is culturally appropriate. This may include engaging a Māori artist, creative, or designer, seeking advice from a Māori language or cultural expert, or undertaking some other form of engagement with Māori.

3.2. Consider engaging a Māori artist, creative, or designer

3.2.1. If you are thinking about using Māori artwork or designs in a trade mark, consider consulting or commissioning an artist, creative, or designer who is familiar with traditional Māori culture and tikanga. This will give you the best chance of ensuring the use or registration of your trade mark is unlikely to offend Māori. To help the artist, creative, or designer create or suggest a trade mark that is unlikely to offend Māori, tell them about the goods or services you intend to use the mark for, and explain that you are seeking sole use of the work as a trade mark.

3.3. Consider engaging a Māori language or cultural expert

3.3.1. If you are thinking about using Māori words or designs in a trade mark, you could also consider working with a Māori language expert or a Māori cultural expert, to help ensure your use is consistent with traditional Māori culture and tikanga and therefore unlikely to offend Māori.

3.4. Consider some other form of engagement with Māori

3.4.1. Māori culture is a living, dynamic, creative, and evolving culture with diverse views among iwi, hapū, Māori collectives (including urban Māori collectives), and other Māori groups. For example, iwi differences exist and the outlook of one iwi may not be that of others.

3.4.2. Effective engagement with iwi and other Māori groups requires recognition that elements of Māori culture are collectively shared and the acquisition of exclusive rights to use any such matter is at odds with this view. However, by engaging with Māori – in particular, relevant iwi, hapū, or whānau – the context of collective responsibility is maintained, and the trade mark owner may be able to proceed with the proposed trade mark with confidence that it is unlikely to offend, having gained the trust of the broader community or the kaitiaki of the relevant taonga.

3.4.3. There is no legal requirement to engage with Māori. If you decide to engage with Māori, to engage effectively you will need to discuss specific details of the mark, including the background that led to adoption (or proposed adoption) of the mark, the list of goods and/or services for which the mark will be used, and any other relevant information about your use (or proposed use) of the mark. Engagement with Māori would ideally result in permission to use element(s) of Māori culture as part of the mark, or confirmation that the use (or proposed use) is unlikely to be offensive to Māori.

3.5. Useful resources

3.5.1. Te Arawhiti has produced a resource to assist those who wish to engage with Māori. This resource can be found on the Te Arawhiti website:

Building closer partnerships with Māori – Te Arawhiti

3.5.2. For Māori geographic place names, contacting the iwi or other Māori groups connected to the location would be a good starting point. The regional council for the area may have resources that identify which iwi, hapū, or whānau it consults with on matters relating to the area in which the geographic place is contained.

3.5.3. A directory of iwi and other Māori organisations may be found on the Te Puni Kōkiri website:

3.5.4. Te Taura Whiri I te Reo Māori, the Māori Language Commission, provide helpful resources for translators as well as support with translation efforts.

3.5.5. Te Mātāwai is an independent entity that works in partnership with the Crown to revitalise the Māori language, and provides resources for regional language development.

3.5.6. The Māori Maps project organises information about ancestral, tribal marae across New Zealand. It is managed by the Te Potiki National Trust, a charitable organisation.

3.5.7. Aratohu Mātauranga Checklist3

3.5.7.1. The Committee and IPONZ have developed the ‘Aratohu Mātauranga Checklist’ (“the Checklist”). The Checklist comprises a series of questions on the process for selection of a trade mark, the meaning of the mark, the origin and significance of the mark, who designed the mark, any consultation that has taken place, whether permission has been obtained to use the mark in relation to the specified goods or services, etc.

Aratohu Mātauranga checklist [PDF, 349 KB]

3.5.7.2. The Checklist can be used to help consider whether including Māori elements within a trade mark could result in a mark whose use or registration might be offensive to Māori. Anyone is welcome to make use of the Checklist as an optional tool to help think through possible issues. For trade mark applicants, completing the Checklist is not a statutory requirement, and is entirely voluntary.

4. Examination of applications for trade marks that contain, or appear to derive from, elements of Māori culture

4.1. All trade mark applications received by IPONZ are assessed to determine whether the mark is, or appears to be, derivative of a Māori sign.4 A trade mark that consists of or contains an element of Māori culture, or that appears to derive from an element of Māori culture, is considered a Māori sign, or derivative of a Māori sign.

4.2. All applications to register trade marks that consist of or contain elements of Māori culture (or appear to derive from elements of Māori culture) go through the same consideration process, regardless of the cultural background of the applicant.

4.3. If the trade mark consists of or contains elements of Māori culture, or appears to derive from elements of Māori culture, then the following will happen:

4.3.1. IPONZ will send the application to the Committee for their consideration.

4.3.2. For national trade mark applications, IPONZ will advise the applicant the application has been forwarded to the Committee.

4.3.3. The Committee will consider the application and communicate its advice to IPONZ. The Committee members use a voting system to provide their advice. The Committee meets quarterly to discuss controversial applications.

4.4. When advice has been received from the Committee, an examiner will consider the advice and conduct a full examination of the application. The examiner will notify the applicant in a report if a section 17(1)(c) objection is being raised.

4.5. While the Act does not require the Commissioner to follow the advice of the Committee, the examination team’s usual practice is to follow the Committee’s advice in relation to section 17(1)(c) objections.

4.6. Where the examiner’s report indicates the mark is considered likely to offend Māori, the applicant will be given the opportunity to respond. If the applicant responds, the examiner will reassess the section 17(1)(c) objection in light of the applicant’s response.

4.7. If the examiner is unsure whether the applicant’s response overcomes the section 17(1)(c) objection, the examiner may refer the application back to the Committee for further advice.

5. Guidance from the Māori Trade Marks Advisory Committee

5.1. General guidance

5.1.1. Section 17(1)(c) of the Act does not define what is likely to offend Māori. The Committee provides advice to the Commissioner, to help the Commissioner decide whether the Commissioner considers the use or registration of the trade mark is likely to offend Māori.

5.1.2. Many general concepts guide the Committee in providing its advice to IPONZ, including the recommendations contained in Ko Aotearoa Tēnei – the report on the Wai 262 claim by the Waitangi Tribunal.

5.1.3. If a trade mark containing or derived from Māori elements is not used in a manner that fits with Māori cultural practices or Māori considerations for commercial use, the use may be perceived as so disrespectful and insensitive that it is likely to offend Māori. There are also potential issues around the granting of a right to exclusively use certain elements of Māori culture, as this is generally at odds with the concept of collective ownership and benefit of mātauranga – especially where there is no acknowledgement of Māori origins or sources that are critical to the product or service.

5.1.4. Some words carry significant meaning that may only be appropriate for Māori to use because there are cultural practices associated with that word. Māori communities often feel strongly about the correct use of such words in accordance with the correct Māori cultural practice – holding the belief that the words may only be used in a Māori setting by Māori communities.

5.1.5. Offensiveness represents a threshold, the determination of which is both objective and subjective. Offensiveness sits along a continuum, which simplistically is represented by acceptable at one end and unacceptable at the other. As society changes, so too does the offensiveness threshold. Recent societal changes include the Māori Orthographic Convention standards established by Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori, which amongst other things encourage the appropriate use of macrons. Failing to use macrons appropriately may result in an undesired meaning being conveyed, sometimes with negative or offensive consequences.

5.1.6. Obtaining specialist advice or engaging with Māori will help those seeking to use elements of Māori culture within trade marks to do so with understanding and respect, in a manner that is unlikely to offend.

5.2. Specific guidance for trade mark applicants

There are many reasons why the Committee may advise the Commissioner that a trade mark is likely to offend Māori. Indicated below are some issues that might arise

5.2.1. Use of Te Reo Māori and tikanga associated with Māori words (kupu)

Te Reo Māori is an oral language, which now has written forms, including dialectal variations. Macrons or double vowels are used to assist with the correct pronunciation and writing of Māori words, and do not detract from the cultural origins of the Māori language as a taonga.

Te Reo Māori is a taonga under Te Ture mō Te Reo Māori 2016 / the Māori Language Act 2016. From a Māori perspective, Te Reo Māori and tikanga Māori cannot be divorced from each other.

Māori words are assessed with reference to the cultural context from which they derive, including if they are stylised. Each word has a unique and specific whakapapa, and mātauranga that describes how the word originated, any dialectal variations, and how usage of the word has developed and changed over time, including the way in which the word relates to, interprets, and explains the world around humankind.

Applicants need to be aware that the use of macrons or double vowels in a written kupu in a trade mark may change the meaning of the word. Applicants should take care to ensure the written expression of the word in their mark has the correct (intended) meaning.

Applicants should also try to ensure their use and registration of Te Reo Māori in trade marks is consistent with any tikanga associated with the word(s). Failure to do this could result in the use or registration of the trade mark being considered offensive to Māori.

Te Reo Māori retains its status as a taonga in whichever form in which it is used. If a word is a spelling variation of kupu Māori or alludes to kupu Māori phonetically, it will be treated as kupu Māori. For example, FAKAPAPA (whakapapa) or MARRNUKA (mānuka) will be treated as kupu Māori and may be considered offensive.

5.2.2. Tapu / Noa

The concepts of tapu and noa are explained in paragraph 1.2.6 above.

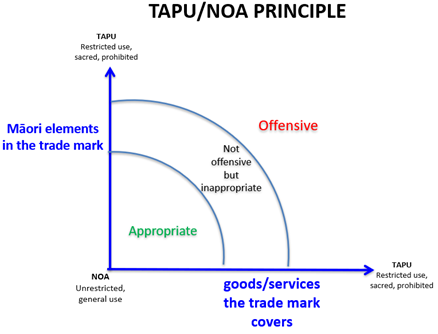

The Tapu/Noa Principle diagram below can provide some assistance in determining whether the use of elements of Māori culture in a trade mark might offend.

*Diagram adapted by the Māori Trade Marks Advisory Committee, from a Kaupapa Māori (Māori Values) assessment matrix for Māori trade marks produced by Grant Bulley, and based on an original sketch by Pare Keiha.

5.2.3. Māori geographical place names

Iwi and other Māori groups have a special connection to the land from where their ancestors originate. It follows that Māori geographical place names - such as names of tribal mountains, rivers, lakes, regions, or geographical landmarks - generally have special significance to Māori. Such geographical names may be regarded as being tapu.

Therefore, the registration of trade marks that comprise or contain Māori geographical names may require consultation with, and permission from, the relevant iwi, other Māori group or Māori authorities. Without this consultation and permission, the mark may be considered offensive to Māori. These trade marks will be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Applicants should be aware that one trader having exclusive rights in a Māori geographical name may conflict with Te Ao Māori principles, including Māori views of collective ownership, and there may be other broader Te Ao Māori, mātauranga, or tikanga concerns. For example, an objection may be raised if a Māori geographical name is used in relation to burial services, gambling, alcohol, cannabis-based products, nicotine-based products, or tobacco-based products.

Seeking advice from an appropriate Māori advisor may help applicants who are considering using trade marks that contain Māori geographical names to avoid offending Māori, and is highly recommended.

5.2.4. Images of geographical landmarks or features of cultural significance

Many New Zealand geographical landmarks and geographical features have cultural significance for Māori. The use or registration of a trade mark that contains images of these geographical landmarks or geographical features is likely to cause offence unless the applicant has obtained permission from the relevant iwi, other Māori group or Māori authorities.

5.2.5. Wāhi tapu

A trade mark that refers to wāhi tapu (a place sacred to Māori in the traditional, spiritual, religious, ritual, or mythological sense, or a site of significance to Māori) is likely to offend Māori and even consultation with relevant iwi, other Māori groups or Māori authorities may not overcome the objection.

For example, an objection is likely to be raised if the mark includes the place where Kupe’s anchor was found (Kumanga Point).

5.2.6. Inappropriate inference

Associating some goods and services with elements of Māori culture may convey an inappropriate inference that could cause offense. If using Māori elements in a trade mark in relation to goods or services appears to make inappropriate assumptions about Māori, this may result in the use or registration of the mark being considered offensive to Māori.

For example, the use of a mark containing Māori elements on alcohol, tobacco, genetic technologies, gaming, or gambling may be considered offensive to Māori. As an illustration of this, the following trade mark would be considered offensive on 'alcoholic beverages’ in class 33:

Historical examples of uses of trade marks containing Māori elements that would be considered offensive to Māori today:

Goods: “ale and stout” (1914)

Goods: “Worcester sauce, pickles and chutney” (1927)

Goods: “cigarettes” (1931)

*Historical examples from Well Made New Zealand: A Century of Trade Marks, Richard Wolfe, Reed Methuen, 1987.

5.2.7. Ngā atua and tūpuna

Tūpuna (Māori ancestral names) or atua (Māori deities) are associated with collective ancestry for Māori. The use of tūpuna or atua are considered tapu because of this. If a trade mark includes tūpuna or atua, a section 17(1)(c) objection is very likely to be raised.

An objection will be raised if the mark includes Ranginui or Papatūānuku, for example.

5.2.8. Taonga, including taonga species

The use and registration of trade marks that comprise or contain the name or representation of taonga may be considered likely to offend Māori, whether the taonga are naturally occurring resources, taonga species, or other taonga, such as maunga, awa or marae.

The registration of a trade mark that comprises or contains the name or representation of a taonga may require consultation with, and permission from, the relevant iwi, other Māori group or Māori authorities. Without consultation and permission, the mark may be considered offensive to Māori.

Generally, the use of a trade mark without consultation and permission that consists only of the name of a taonga (either without any stylisation or with minimal stylisation), or a photograph or lifelike representation of a taonga, is likely to cause offence. Applicants are likely to be asked whether they have consulted with the relevant Māori group, and whether permission has been obtained. Applicants should also be aware that one trader having exclusive rights in such a mark may conflict with Te Ao Māori principles, including Māori views of collective ownership, and there may be other broader Te Ao Māori, mātauranga, or tikanga concerns, including concerns related to the appropriate use of the taonga.

5.2.8.1 Taonga species

Taonga species are the native flora and fauna of New Zealand, including microbes and genetic resources.

Taonga species have cultural references and associated practices for Māori, and are associated with collective ancestry, mātauranga and tikanga. A trade mark that consists solely of the name of a taonga species will be considered tapu because of this. One trader having exclusive rights in a mark consisting solely of the name of a taonga species conflicts with Māori views of collective ownership. There is no single authority who can provide consent for the use of a taonga species in a trade mark. For these reasons, a mark consisting solely of the name of a taonga species is likely to be considered offensive to Māori.

Trade marks that include the name of a taonga species in combination with other material, including other taonga species and/or stylised representations of the name of the taonga species, will be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

For example, kiwi is a taonga species. Marks that consist solely of the word ‘kiwi’ will be considered offensive to Māori. Marks that include the word ‘kiwi’ in combination with other material, including stylised representations of the word ‘kiwi’, will be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

5.2.8.2 Haka Ka Mate

The haka Ka Mate (“Ka Mate”) is a taonga.

Through the Haka Ka Mate Attribution Act 2014, the Crown expressly acknowledges the significance of Ka Mate, Te Rauparaha as the composer of Ka Mate, and the role of Ngati Toa Rangatira (“Ngati Toa”) as the kaitiaki of Ka Mate.

The registration of a trade mark that comprises or contains the words, actions and/or choreography of Ka Mate, or excerpts thereof, is likely to require consultation with, and permission from, Ngati Toa. Without consultation and permission, the mark may be considered offensive to Māori.

More information about Ka Mate and The Haka Ka Mate Attribution Act 2014 can be found on the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) website:

Haka Ka Mate Attribution Act guidelines – MBIE

5.2.8.3 Pounamu

Pounamu is a prized greenstone found in Te Waipounamu, the South Island of New Zealand. Pounamu is a taonga. Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu (Ngāi Tahu) is the kaitiaki (guardian) of this taonga.

The Ngāi Tahu (Pounamu Vesting) Act 1997 formally made Ngāi Tahu responsible for the ownership and management of pounamu.

The registration of a trade mark that comprises or contains the word ‘pounamu’, or a representation of pounamu, may require consultation with, and permission from, Ngāi Tahu. Without consultation and permission, the mark may be considered offensive to Māori.

More information about the Ngāi Tahu (Pounamu Vesting) Act 1997 can be found on the Ngāi Tahu website:

Pounamu – Te Rūnanga o Ngāi Tahu

5.2.8.4 Te Awa Tupua

Te Awa Tupua is the name for the Whanganui River. Te Awa Tupua is a taonga.

The Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act 2017 declares Te Awa Tupua is a legal person. Te Pou Tupua is appointed to be the human face of Te Awa Tupua and to act in the name of Te Awa Tupua.

The registration of a trade mark that comprises or contains the words ‘Te Awa Tupua’ may require consultation with, and written permission from, Te Pou Tupua. Without consultation and permission, the mark may be considered offensive to Māori.

5.2.8.5 Parihaka

Parihaka is the name of a community in South Taranaki, founded by Māori chiefs Te Whiti o Rongomai and Tohu Kākahi on land seized by the government during the post-New Zealand Wars land confiscations of the 1860s. The village embraced Māori who had been dispossessed of their land by confiscations, offering refuge supported by its extensive gardens that produced sufficient food to feed its inhabitants and visitors.

Parihaka is a taonga.

The registration of a trade mark that comprises or contains the word ‘Parihaka’ may require consultation with, and written permission from, the trustees of the Parihaka Papakāinga Trust. Without consultation and permission, such a mark may be considered offensive to Māori.

5.2.9. Māori artwork and design

Traditional Māori art and designs form an important part of Māori identity and culture as they communicate a story and have meaning and significance. Trade marks containing or comprising Māori artwork and designs (including photographs of such works) may be considered offensive if the context in which they will be used is considered sufficiently inappropriate and/or permission to use the works has not been obtained. See paragraph 5.2.2 above, where the tapu/noa principle is discussed.

For example, using Māori kowhaiwhai from a specific wharenui on underwear is likely to be considered offensive to Māori.

5.2.10. Tikanga Māori

Māori artists often dedicate themselves to studying a specific art form. Part of this study includes learning tikanga, or the ‘right’ way to do things.

Where a trade mark contains or comprises Māori artwork or designs, as part of considering whether the mark is offensive to Māori, the Committee will consider whether respect for the tikanga has been demonstrated in arriving at the design of the proposed trade mark. Consulting or commissioning a Māori artist or designer is highly recommended, as this is likely to result in a trade mark that will not offend Māori (see paragraph 3.2.1 above).

5.2.11. Use of certain Māori words (kupu)

Seeking exclusive use of some kupu could be at odds with how Māori may have intended to use the kupu in terms of tikanga or customary use. For this reason, it is beneficial for applicants to have a thorough knowledge of the origins, history, and whakapapa of any kupu before a trade mark incorporating kupu is used or registered.

Trade marks that contain kupu which have significant tikanga associated with them will be considered on a case-by-case basis. To avoid the use or registration of the mark being considered likely to offend Māori, the applicant may need to show that they are working within, and honouring, the tikanga of such a kupu.

For example, the Committee advises that the kupu ’ariki’ is an important kupu that is strongly associated with tikanga. In addition, ‘ariki’ is a word with mana and is therefore tapu. See paragraph 5.2.2 above, where the tapu/noa principle is discussed. A trade mark that contains the kupu ‘ariki’ is likely to be considered offensive if it is used on goods or services that are noa, or if there are concerns the use of the mark may not work within, and honour, the tikanga of the kupu ‘ariki’.

5.2.12. Whakataukī, whakatauākī, and kīwaha

Whakataukī, whakatauākī, and kīwaha are types of phrases that are used in specific contexts or may have a close association with an iwi or other Māori group.

An application to register a trade mark that contains whakataukī, whakatauākī and/or kīwaha may be considered offensive unless the applicant has consulted with the relevant iwi or other Māori group.

5.2.13. Māori words (kupu) that have mana

Some kupu have mana (high importance) because of a close association with a whānau, hapū, iwi, or taonga. The use or registration of a trade mark that contains such a kupu may be considered offensive unless the applicant has consulted with the relevant iwi or other Māori group.

5.2.14. Māori words and their English translation

As mentioned in paragraph 5.2.1, Māori words are assessed with reference to the cultural context from which they derive. While the English translation of a particular Māori word may not cause offence, sometimes the Māori word has another layer of meaning or understanding that needs to be considered.

For example, the word ‘kuia’ could be translated as ‘grandmother’. This translation is accurate, however it doesn’t reflect the full significance of the word ‘kuia’ for Māori. In Māoridom, kuia is a name used to show great respect — recognising a person’s achievements, wisdom, and contribution. In light of this association, it would be offensive for the word ‘kuia’ (tapu) to be used in a trade mark on goods like food and alcohol (noa). See paragraph 5.2.2 above, where the tapu/noa principle is discussed.

5.2.15. Māori words that are also words in other languages

There are words in other languages that are also Māori words. When considering whether the use or registration of a trade mark is likely to offend Māori, any word in the mark will be interpreted from a Māori perspective. This means that if there is a foreign word in the mark that also has a meaning in Māori, the assessment about offensiveness to Māori will be based on the meaning of the Māori word.

Examples:

- In Japanese ‘amaru’ means ‘to remain, to be left over, to be in excess’, however, in Māori ‘amaru’ is defined as ‘dignified’.

- The Kiwi vernacular ‘mate’ is associated with death if read as a kupu Māori.

5.2.16. Images or designs common to other cultures

The same image or design element may be used in a number of different cultures. When considering whether the use or registration of a trade mark is likely to offend Māori, any image or design in the mark will be interpreted from a Māori perspective.

For example, a spiral intended to evoke Greek culture will be interpreted as a koru Māori when determining whether the use or registration of the mark is likely to offend Māori.

5.2.17. Awareness of community views and potential opposition

With growing awareness and promotion of Māori language, knowledge, and content in New Zealand, concerns around the misappropriation or dishonouring of Māori content and Māori culture are becoming more prominent. Awareness of publicly expressed opinions and views, including on social media, may inform the advice the Committee gives to the Commissioner.

For example, if the Committee is aware that Māori communities, iwi leaders, or kaitiaki of taonga have raised concerns or objections to the use of a particular element of Māori culture, and the trade mark contains that element of Māori culture, the Committee may mention its awareness of Māori views in the advice it gives to the Commissioner, and such a mark may be considered likely to offend Māori.

5.3. Examples of trade marks that may receive a section 17(1)(c) objection

Applicants should not refer to previous registrations of trade marks containing Māori elements for guidance as to what might be considered acceptable. As noted earlier, Māori perspectives are dynamic. The fact that a particular trade mark was not considered offensive at an earlier time does not mean the same trade mark will be considered unlikely to offend Māori in a later application. All applications to register trade marks that contain elements of Māori culture (or elements that appear to derive from Māori culture) are referred to the Committee, who will advise whether the mark is likely to offend Māori. The Commissioner will consider the Committee’s advice. After doing so, the Commissioner may decide that the use or registration of the mark is likely to offend Māori.

The table below provides a few examples of trade marks that may receive a section 17(1)(c) objection based on their likelihood to offend Māori.

| Problematic trade mark | General principle(s) |

|---|---|

|

Specification: 'Bread' in class 30 |

Tapu / Noa - See 1.2.6 and 5.2.2 Ngā atua – See 5.2.7 |

|

KAWAKAWA Specification: 'Electronic cigarettes' in class 34 |

Tapu / Noa - See 1.2.6 and 5.2.2 Inappropriate inference - See 5.2.6 Taonga species - See 5.2.8.1 |

|

Tāmaki Makaurau Painters Specification: 'Painting services' in class 37 |

Māori geographical place names - See 5.2.3 |

Specification: 'Travel arrangement' in class 39 |

Images of geographical landmarks or features of cultural significance - See 5.2.4 |

*Mitre Peak photo © Mark Roberts 2022. Adapted from original and used with permission.

5.4. Overcoming the objection

5.4.1. In some situations it may be possible to overcome an offensiveness objection through consultation with Māori, provided this results in either permission being granted or confirmation that there would be no offense.

5.4.2. In some situations it may be possible to overcome the objection by amending the specification of goods and services. For example, if a trade mark was considered offensive because it contained a tapu word to be used on goods that are considered noa, deleting the noa goods from the goods and services specification may overcome the objection.

5.5. Other considerations

5.5.1. If a trade mark containing or comprising elements of Māori culture is not considered offensive to Māori, the Commissioner may still refuse to register the trade mark for other reasons. For example, registration may be refused if the mark is descriptive of the goods or services for which registration is sought5, or because the mark is the same or similar to a trade mark that already exists on the register6.

5.5.2. Applicants should also be aware that if the Commissioner accepts a trade mark for registration, this does not preclude interested parties, including Māori entities, from opposing the use and registration of the trade mark on the grounds its use or registration is likely to offend Māori. Applicants should note that there may be divergent views in relation to the use and registration of trade marks that contain or comprise elements of Māori culture.

Glossary

| aroha | affection, sympathy, charity, compassion, love, empathy |

| atua | deity |

| awa | river, stream, creek, canal or other waterway |

| hapū | kinship group |

| iwi | tribal group |

| kaitiaki | guardian, custodian, steward, including the associated responsibilities of the guardian / custodian / steward |

| kīwaha | idiom |

| kupu | word |

| mana | prestige, authority, control, power, influence, status, spiritual power |

| Māori | Indigenous People of Aotearoa New Zealand |

| marae |

'marae' may refer to either:

|

| mātauranga |

often translated as Māori knowledge, wisdom, understanding, and skill.

|

| maunga | mountain, mount, peak |

| mauri | life principle, life force, vital essence |

| moko | Māori tattooing designs on the face or body done under traditional protocols |

| Papatūānuku | Earth Mother |

| pono | to be true, valid, honest, genuine, sincere |

| pounamu | New Zealand greenstone, nephrite jade |

| rangatiratanga | right to exercise authority, sovereignty, self-determination |

| Ranginui | Sky Father |

| raranga | weaving |

| tā moko | to tattoo or apply a traditional tattoo |

| tangata whenua | Māori, people of this land by right of first discovery |

| taonga | treasure |

| taonga tuku iho | heirloom, something handed down, cultural property, cultural heritage |

| tapu | be sacred, prohibited, restricted |

| Te Ao Māori | Māori world view |

| Te Reo Māori | Māori language |

| Te Tiriti o Waitangi | The Treaty of Waitangi |

| Te Ture Mō Te Reo Māori 2016 | The Māori Language Act 2016 |

| tika | truth, correctness, directness, justice, fairness, righteousness |

| tikanga | protocols |

| Toi Māori | traditional and modern Māori arts including raranga, whakairo rākau, kowhaiwhai, whare whakairo, tā moko, rock art and other forms of Māori visual art |

| tupuna | ancestors, grandparents |

| wāhi tapu | sacred places |

| whakapapa | genealogy or lineage |

| whānau | family group, including extended family group |

| whanaungatanga | kinship connections |

| whakatauākī | proverbs where the author is known |

| whakataukī | proverbs |

| wharenui | meeting house, main building of a marae where guests gather or are accommodated |

Appendix

1.1. Further resource material for understanding

1.1.1. General

Te Wakaminenga (The Confederation of Chiefs) / He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni – Declaration of the Independence of New Zealand 1835

The Mataatua Declaration on Cultural and Intellectual Property Rights of Indigenous Peoples - https://ngaaho.maori.nz/cms/resources/mataatua.pdf

Aroha Te Pareake Mead, Ngā Tikanga, Ngā Taonga - Cultural And Intellectual Property: The Rights Of Indigenous Peoples (Research Unit for Māori Education, University of Auckland, Auckland NZ, 1994).

Māori Trade Mark Focus Group, Ministry of Commerce (Now Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment), Māori and Trade Marks: A Discussion Paper (Ministry of Commerce, Wellington NZ, 1997). ISBN 0478003803 (pbk).

Margaret Rose Orbell, The Illustrated Encyclopedia Of Māori Myth And Legend (Canterbury University Press, Christchurch NZ, 1995). ISBN 0908812450 (hbk).

Puna Web Directory Māori Subject List (archived May 2016) - https://natlib.govt.nz/about-us/open-data/te-puna-web-directory-metadata

Tuhi Tuhi Communications, Takoa 2002ad Te Aka Kumara O Aotearoa: A Directory Of Māori Organisations And Resource People (Tuhi Tuhi Communications, Auckland NZ, 2002). ISBN 0473085623 (pbk).

Wises Publications Limited, Discover New Zealand: A Wises Guide (Wises Publications, Auckland NZ, 1994).

Bateman NZ Historical Atlas - Visualising New Zealand Ko Papatuanuka e Takoto Nei ISN 1 86953 335 6

United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples - https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_en.pdf

Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori – The Māori Language Commission - https://www.tetaurawhiri.govt.nz/

Te Matawai – https://www.tematawai.maori.nz/

1.1.2. Māori customary concepts – Tikanga Māori

Anne Salmond, Hui: A Study Of Māori Ceremonial Gatherings (A. H. & A. W. Reed, Wellington NZ, 1975).

Angela Ballara, Iwi: The Dynamics Of Māori Tribal Organisation From c.1769 To c.1945 (Victoria University Press, Wellington NZ, 1998). ISBN 0864733283 (pbk).

Cleve Barlow, Tikanga Whakaaro: Key Concepts In Māori Culture (Oxford University Press, Auckland NZ, 1991). ISBN 0195582128 (pbk).

Elsdon Best, The Māori As He Was: A Brief Account Of Māori Life As It Was In Pre-European Days (Government Printer, Wellington NZ, 1974).

Elsdon Best, Māori Religion And Mythology: Being An Account Of The Cosmogony, Anthropogeny, Religious Beliefs And Rites, Magic And Folk Lore Of The Māori Folk Of New Zealand. (Government Printer, Wellington NZ, 1976-1982). ISBN 0909010360.

J Patterson, Exploring Māori Values (Dunmore Press, Palmerston North NZ, 1992). ISBN 0864691564 (pbk).

James Irwin, An Introduction To Māori Religion: Its Character Before European Contact And Its Survival In Contemporary Māori And New Zealand Culture (Australian Association for the Study of Religions, Bedford Park Sth Australia, 1984). ISBN 0908083114 (pbk).

Michael King, Te Ao Hurihuri: Aspects of Māoritanga (Reed, Auckland NZ, 1992). ISBN 0790002396 (pbk).

Michael P Shirres, Te Tangata: The Human Person (Accent Publications, Auckland NZ, 1997). ISBN 0958345414 (pbk).

Peter Henry Buck, The Coming Of The Māori (Māori Purposes Fund Board, Wellington NZ, 1950).

R J Walker, Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle Without End (Penguin Books, Auckland NZ, 1990). ISBN 0140132406 (pbk).

Sidney M Mead, Customary Concepts Of The Māori: A Sourcebook For Māori Students (Dept. of Māori Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington NZ, 1984).

Sidney M Mead, Neil Grove, Ngā Pepeha A Ngā Tipuna: The Sayings Of The Ancestors (Victoria University Press, Wellington NZ, 2001). ISBN 0864733992 (hbk).

Rangimarie Rose Pere, Ako: Concepts And Learning In The Māori Tradition (Dept. of Sociology, University of Waikato, Hamilton NZ, 1982). ISBN 0959758348 (pbk).

1.1.3. Toi Māori

D R Simmons, Tā Moko: The Art Of Māori Tattoo (Reed Books, Auckland NZ, 1986). ISBN 0474000443 (pbk).

David Simmons, Whakairo: Māori Tribal Art (Oxford University Press, Auckland NZ, 1994). ISBN 0195581199 (pbk).

Rangihiroa Panoho, Māori Art: history, architecture, landscape and theory, Bateman, Auckland, 2015.

Ngarino Ellis, A Whakapapa of Tradition: 100 years of Ngati Porou Carving 1830-1930, AUP, Auckland, 2016.

Hans Neleman, Moko Māori Tattoo (Edition Stemmle, Zurich, c1999). ISBN 3908161967.

Janet Davidson, D C Starzecka, Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, Māori: Art And Culture (D. Bateman, in association with British Museum Press, Auckland NZ, 1996). ISBN 186953302X.

J H (John Henry) Menzies, Māori Patterns Painted And Carved (Hagley Press, Christchurch NZ, 1975).

Links, examples and information regarding Māori art at https://www.maoriart.org.nz/

Mick Pendergrast, Raranga Whakairo Māori Plaiting Patterns (Coromandel Press, Coromandel NZ, 1984). ISBN 0908632959 (pbk).

Pita Graham, Māori Moko Or Tattoo (Bush Press, Auckland NZ, 1994). ISBN 0908608632 (pbk).

Sandy Adsett, Chris Graham, Rob McGregor, Kōwhaiwhai Arts (Education Advisory Service - Art & Design, Tauranga NZ, 1992). ISBN 0477015999 (pbk).

Sidney M Mead, The Art Of Māori Carving (Reed, Auckland NZ, 1961). ISBN 079000366X (pbk).

Terence Barrow, An Illustrated Guide To Māori Art (Reed, Auckland NZ, 1995). ISBN 0790004100 (pbk).

W J (William John) Phillipps, Māori Rafter and Taniko Designs (Harry H. Tombs, Wellington NZ, 1960).

Footnotes

1 Trade Marks Act 2002, s 177.

2 Trade Marks Act 2002, s 178.

3 Name gifted by Te O Kahurangi Waaka.

4 Trade Marks Act 2002, s 178.

5 Trade Marks Act 2002, s 18.

6 Trade Marks Act 2002, s 25.